The US space agency’s Perseverance robot has left Earth on a mission to try to detect life on Mars.

Artwork: Did Mars ever host life? The evidence could be held in the planet’s rocks

The one-tonne, six-wheeled rover was launched out of Florida by an Atlas rocket on a path to intercept the Red Planet in February next year.

When it lands, the Nasa robot will also gather rock and soil samples to be sent home later this decade.

Perseverance is the third mission despatched to Mars inside 11 days, after launches by the UAE and China.

Lift-off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station occurred at 07:50 local time (12:50 BST; 11:50 GMT).

Nasa made this mission one of its absolute priorities when the coronavirus crisis struck, establishing special work practices to ensure Perseverance met its launch deadline.

“I’m not going to lie, it’s a challenge, it’s very stressful, but look – the teams made it happen and I’ll tell you, we could not be more proud of what this integrated team was able to pull off here, so it’s very, very exciting,” Administrator Jim Bridenstine told reporters.

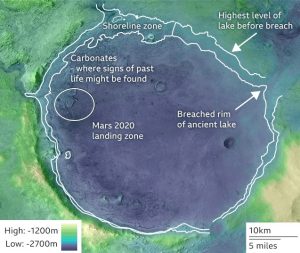

Perseverance is being targeted at a more-than 40km-wide, near-equatorial bowl called Jezero Crater.

Satellite images suggest this held a lake billions of years ago.

Scientists say the rocks that formed in this environment stand a good chance of retaining evidence of past microbial activity – if ever that existed on the planet.

Perseverance will spend at least one Martian year (equivalent to roughly two Earth years) investigating the possibility.

Unlike the previous four rovers Nasa has sent to Mars, its new machine is equipped to directly detect life – either current or in fossilised form.

But any evidence it uncovers will almost certainly have its sceptics, which is why researchers want to bring whatever Perseverance finds back home for the deeper analysis only sophisticated laboratories on Earth can perform.

The rover will therefore package its most interesting rock discoveries in small tubes. An elaborate mix of future missions will then launch later this decade to try to retrieve these samples.

How is Perseverance different from earlier rovers?

At first glance, Perseverance looks to be a copy of the Curiosity robot Nasa sent to Mars’ Gale Crater in 2012. Indeed, the new robot even incorporates some leftover parts from the earlier mission.

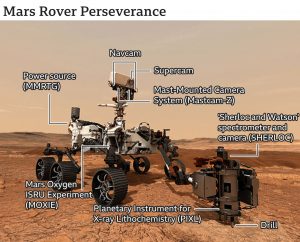

But the seven instruments on Perseverance are either major upgrades or totally new.

Expect some remarkable new imagery from the 23 cameras on the vehicle – and sound, because the Perseverance mission carries microphones as well.

“We hope to capture some of the sounds of entry, descent and landing; and some of the sounds of driving around, merging that with the video we can take,” explained Jim Bell, the principal investigator on the rover’s mast-mounted camera system, MastcamZ.

In addition to geological investigations and the search for life, there’s an emphasis on future human exploration.

The Moxie instrument will practise making oxygen from Mars’ carbon dioxide-dominated atmosphere; and there are even samples of spacesuit material aboard to see how they cope in the planet’s harsh environment.

What role will the Ingenuity helicopter play?

This is purely a technology demonstration. Ingenuity aims to prove that aero vehicles can operate in Mars’s rarefied air.

The 1.8kg machine will be deployed from Perseverance’s belly once a suitable location for its flight experiments has been identified.

Ingenuity’s twin, counter-rotating blades will have to spin extremely fast to get off the ground.

Engineers have five sorties planned over a 30-day period, with the ambition on each excursion of climbing ever higher into the sky and getting further away from Perseverance.

“Today, we simply don’t use the aerial dimension in space exploration, but in future we will,” said Nasa’s Ingenuity project leader, MiMi Aung. “They will be used, for example, in a scouting function. When humans arrive, or indeed future rovers, the rotorcraft will go in front and gather high-definition images of the way ahead,” she told.

Why is Jezero Crater so interesting to scientists?

Jezero is named after a town in Bosnia-Herzegovina. In some Slavic languages the word “jezero” also means “lake” – which should explain the fascination.

This 500m-deep bowl once saw huge volumes of water flow in through the western wall to pool on the crater floor.

Where the water entered, it even deposited sediments to form a delta. Perseverance will try to land next to this feature.

Jezero displays multiple rock types, including clays and carbonates, that have the potential to preserve the type of organic molecules that would hint at life’s bygone existence.

Particularly enticing is the “bathtub ring” of sediments laid down at the ancient lake’s shoreline. It’s here that Perseverance could find what on Earth are called stromatolites.

“These are ancient fossilised microbial mats,” explained rover deputy project scientist Katie Stack Morgan.

“They leave behind very thin layers, with concentrations of particular elements and organics at repeated intervals. We’ll be looking for those fine laminations, looking for chemistry and textures you wouldn’t expect if these things were just abiotic, or didn’t involve life.”

How does Perseverance fit into wider Mars goals?

We know from the search for the earliest life on Earth that the evidence can sometimes be controversial.

So, even if Perseverance stumbles across rocks that appear to have been fashioned by some ancient Martian biology, it will almost certainly require confirmation by analytical instruments on Earth that are far superior to the miniaturised versions carried on the rover.

That’s why a key task for Perseverance will be to package its most interesting rocks in small metal canisters and leave them on the Jezero Crater floor.

Nasa and the European Space Agency (Esa) intend to go fetch these tubes with two more missions that are scheduled to leave Earth in 2026.

It’s a remarkable endeavour involving a second rover, a Mars rocket and a huge satellite to ship the sample tubes home, getting them here in 2031. “You can argue that what we’ll be trying to do is as complicated as the Apollo Moon landings – when you think of the complexity of the robotics involved,” David Parker, director of human and robotic exploration at Esa, told BBC News.

“And it will also be a step on the way to sending humans to Mars because the architecture of this Mars Sample Return project is really a scale model of a human mission with its multiple vehicles that have to launch, land, launch again, rendezvous in orbit and return to Earth.”

Nasa and Esa estimate the total cost of getting samples back to Earth, including the $2.7bn (€2.3bn; £2bn) cost of Perseverance, will come to at least $7bn (€6bn; £5.4bn).