TOKYO: As Tokyo’s Paralympics draw to a close and focus shifts to Paris 2024, France is looking for inspiration to the so-called “British model” that has produced Games success.

Team GB is riding high in the medal tables at Tokyo once again, trailing only China in terms of golds.

And London’s Paralympics are widely cited as the benchmark for the biggest international event in para sports.

“We all took note of the success of London 2012. It was a real turning point,” says Tony Estanguet, president of the Paris 2024 organising committee.

“We’ve met their teams and continue to work with them,” he told AFP, adding that he talked during the Olympics with his London 2012 counterpart Sebastian Coe, who now heads World Athletics.

“Their success was about very strong communication,” says Estanguet, citing efforts by both the organising committee, but also the advertising campaign of Paralympic broadcaster Channel 4.

The British channel famously rolled out its Paralympic campaign after the Olympics under the tagline “Thanks for the warm-up”, in an unapologetic celebration of the sporting prowess of Paralympians.

And it has run award-winning television promotions for the Paralympics under the theme “Meet the Superhumans”.

“The investment that Channel 4 has put in us has shown disability in a really positive way,” British sprinter Libby Clegg told AFP.

The two-time silver medallist at Rio began her Paralympic career in Beijing in 2008 and has seen the evolution of coverage and focus on Paralympics.

“It has been great for us as disabled people especially in the UK. It is great to see that this coverage has continued on,” she said.

BRITISH PARALYMPIC HISTORY

And its not just British athletes who feel that way, with French judoka and Tokyo Games flagbearer Sandrine Martinet recalling the famously packed stands in London as a turning point.

“Culturally speaking, we felt the atmosphere was different in London. Something happened during those Games.”

Estanguet credits “a really strong approach to ticketing, based on school audiences, which worked really well”.

And the communication, publicity and ticketing made a tangible difference: While only 18 per cent of Brits could name a Paralympian in 2010, the figure was 41 per cent by the end of the 2012 Games.

Interest in the Paralympics and medal success have gone hand in hand for Britain, which hasn’t come lower than third in the medal table in the last 20 years, and has only slipped below second once.

The Paralympics have a particularly British history, having been invented in the UK’s Stoke Mandeville which hosted the first precursor to the Games in 1948.

But the Brits have also not rested on their laurels, managing to maintain their position even as other countries improve.

That has contributed to a professionalisation of the Games.

“You can’t win a medal here if you train two or three times a week,” points out German long jumper Markus Rehm.

“This has changed.”

“WORK TO DO”

One of the features of the British model has been the integration of disabled athletes into the federations in charge of each sport.

France begun doing the same in December 2016 after a decree issued by the sports ministry.

“What we want is to do sport together,” said Sophie Cluzel, French secretary of state for people with disabilities.

But Stephane Houdet, France’s other Tokyo Paralympics flagbearer and a wheelchair tennis player, believes his country is “still at the start of the road.”

“The Olympic delegation came with 24 staff members, we have three,” he told AFP.

“We don’t have a physio, or a doctor,” he added.

“We still have work to do.”

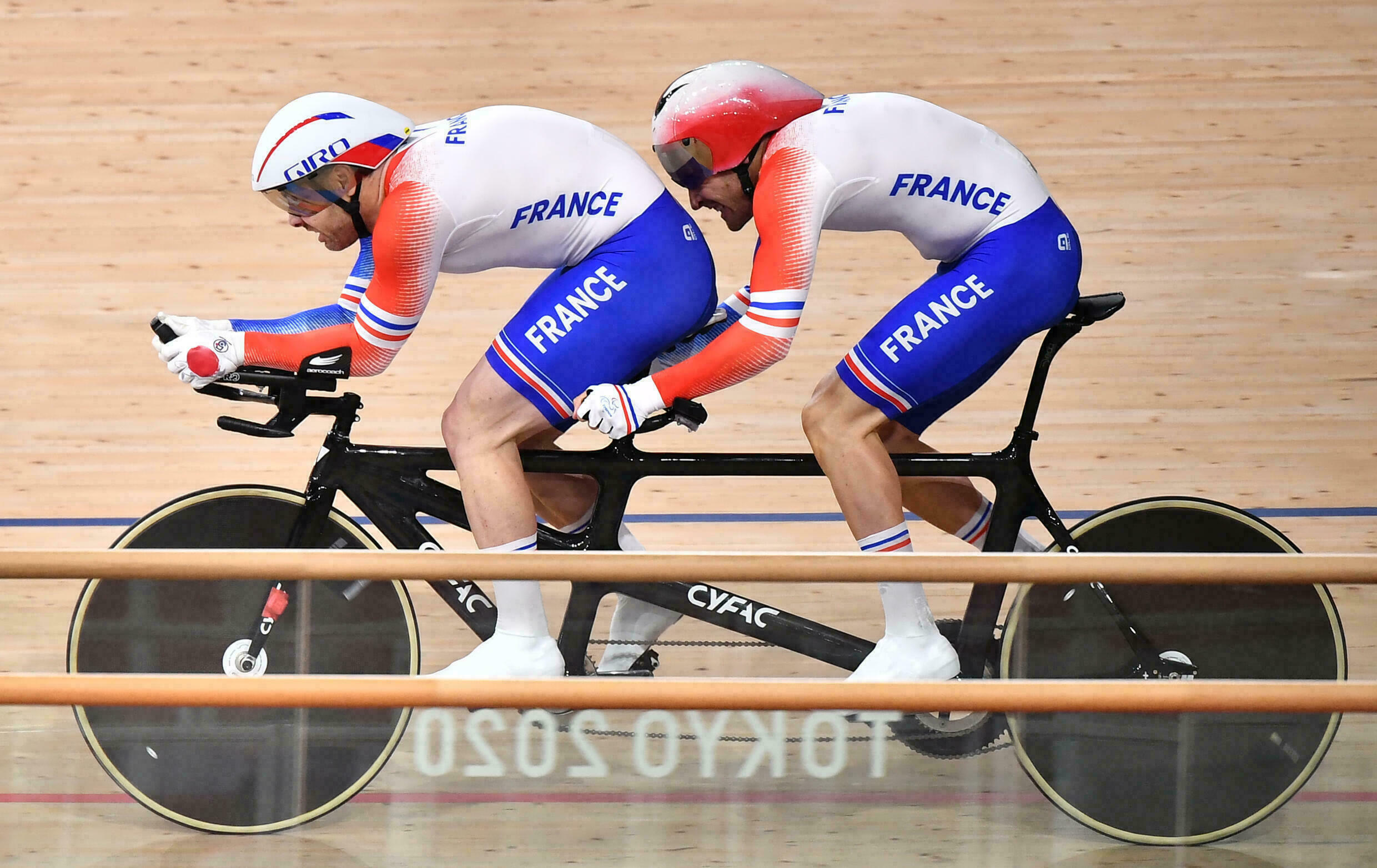

Cyclist Francois Pervis came to parasports as a sighted pilot working with visually impaired Paralympian Raphael Beaugillet and says the British model shows clear results at the Games.

“They put disabled sport on the same level as non-disabled. They share training slots at the national velodrome,” he said.

“If we asked for that, they’d laugh in our face.”